The Category Design Scorecard

How do you know when you’re looking at a category creator versus just another high-growth company?

Arrrrr! 🏴☠️ Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of Category Pirates. Each week, we share radically different ideas to help you design new and different categories. For more: View the mini-book archive | Listen to a category design jam session | Dive into an audiobook | Enroll in the free Category Accelerator email course

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

In a previous letter, we wrote how category design is the strategy for dealing with the “winner take all” reality that has taken hold in business.

We also shared the discovery that only 19 percent of Fortune’s 100 fast-growing companies are category designers. And yet, they captured 51 percent (of the prior three years cumulative) of the revenue growth, and 80 percent (of the prior three years cumulative) of the market capitalization.

But how do you know when you’re looking at a category creator versus just another high-growth company fighting tooth and nail for market share in an existing category?

The Category Design Scorecard will tell you.

We created this scorecard after reviewing companies from the Fortune 100 Fastest-Growing Companies list and analyzing their 10Ks, Annual Reports, Investor Presentations, and Investor Relations websites.

Companies were scored in five key areas on a 0 to 2 scale: 0 being the company does not successfully accomplish each area’s goal, 1 being the company partially accomplishes the goal, and 2 being the company successfully accomplishes the goal.

(Area 1) Category POV: Does the company have a clear “Point of View” of their category? Are they able to frame a powerful problem, articulate a compelling vision, and most importantly, communicate the core compromises, trade-offs, and problems inherent to the way the category is today, such that the consumer/customer will be open to a new and different approach. It’s important to note this should not be expressed as the “challenges” unique to a brand or company, but rather a fundamental problem to the entire category itself that consumers have typically and unnecessarily accepted as a given.

(Area 2) Future Category Reimagined & Without Compromise: Does the company cast a compelling future—free of these fundamental problems, compromises, and trade-offs inherent to the category? Are they able to explain what the category looks like in its true glory where the customer/consumer is transformed, partners are proud participants, and the company generates an abundance and surplus of benefits: rational, emotional, aspirational, as well as financial?

(Area 3) Radically Different Offer + Business Model: How does this new category get delivered to the customer, both through a breakthrough product/service/offer, but also through a breakthrough business model? How does product innovation and business model innovation come together in a way where 1 + 1 = 11?

(Area 4) Data Flywheel: Does the company generate data about customer/consumer demand/preferences (be it intentional or as a side effect) that creates a unique opportunity and advantage to anticipate the future of consumer demand and any category shifts? Does this Data Flywheel provide insight into not only how to improve company offerings, but predict where demand for this new category will unfold next?

(Area 5) Depth & Degree of Customer Outcomes: Does the company generate satisfied/ecstatic customers/consumers? Are they so happy and satisfied they gladly evangelize the product/service to others? Or, even better, do customers want to tell their own stories of radical transformational outcomes—where the customer’s life is truly different after engaging with the company?

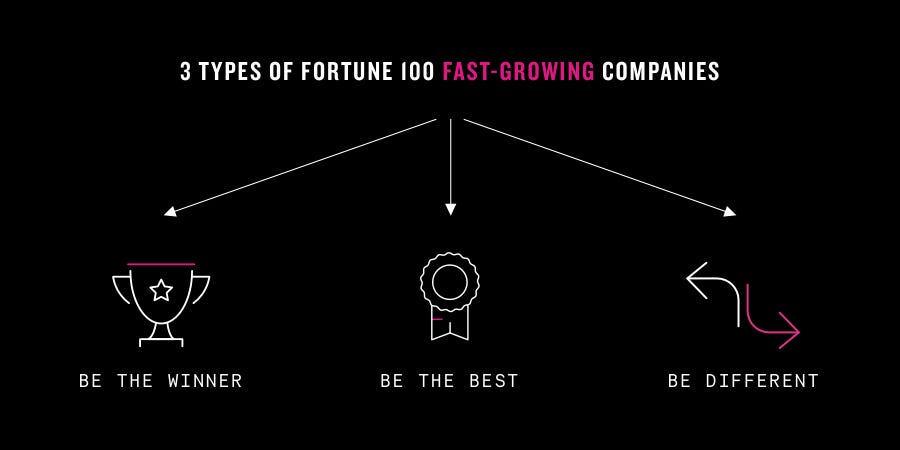

Using The Category Creation Scorecard, companies on the Fortune 100 Fastest Growing list fell into three (3) groups.

60% of companies on the list scored 0 to 2, and were much more focused on “beating the competition” than innovating or creating something entirely new. These “compete to win” companies fight for existing market share.

20% of the companies scored 3 to 5, and were more focused on “being the best” within an existing category—not “being the leader” of a new category.

The final 20% of the companies scored 6 to 10, and were companies clearly trying to design/create a new and meaningfully different category.

What was striking to discover, however, was the three-year stock price growth for each of these three types of companies.

“Be The Winner” companies (0 to 2) saw 21 percent growth. “Be The Best” companies (3 to 5) saw 31 percent growth.

Meanwhile, “Be Different” companies (6 to 10) saw 49 percent growth. Revenue growth was roughly the same across all three buckets of companies, meaning category creators weren’t growing faster per se—but each dollar of revenue generated for category creators was far more valuable.

This is a powerful indication that investors pay for category potential. They understand the company who designs the category is best positioned to dominate it.

After all, it’s the promise of future growth that makes a company valuable, not past performance.

NET-NET, COMPANIES TEND TO CLUSTER INTO 3 BUCKETS

“Be The Winner”

“Be The Best”

“Be Different”

Once you understand the qualities of these three types of companies, you will see them everywhere. Their marketing will ring loud and true—because they announce themselves to the world exactly as they are.

“Be The Winner”: Scores 0-2

Xerox. Delta Airlines. Ford. Verizon.

These are companies that believe strategy = competition.

These Market Share Maniacs have no goal other than to beat their competitors and be the #1 market share leader, believing things like “brand equity” will be the reason why customers pick their products off the shelf.

They play a comparison game.

Financials aside, you can usually tell which companies are playing the “Be The Winner” game because they use words like most-trusted, longest-standing, customer-favorite, award-winning, etc. Whether “Be The Winner” companies realize it or not, these words signal to customers the unchanged nature of their category—and hope, using status, to convince them not to switch to a next-best alternative/competitor.

As a consequence, their scorecard looks as follows:

Category POV/Problem = 0. They don’t see anything wrong with the category and would rather not change.

Future category reimagined = 0. Again, nothing to change, so no reason to educate customers on a different future.

Radically different offer and business model = 0-2. This is likely the only place these companies score. They tend to have a great product, maybe a great business model, or even both. But they have no ambitions beyond this particular area.

Data Flywheel = 0. No need to anticipate future category and/or customer behavior shifts because the overwhelming belief is “the world tomorrow will be the same as it is today.”

Depth & Degree of customer outcomes = 0. Again, the customer is not what they care about. They care about maximizing returns for investors based on their position in the category today.

“Be The Best”: Scores 3-5

In 1997, TIME Magazine named Andy Grove, the CEO of Intel at the time, TIME’s Man of the Year. When Andy Grove passed away in 2016, TIME Magazine said, “He is remembered as a pioneer of the digital age, a savior of Intel and a champion of the semiconductor revolution.”

Andy Grove made Intel so dominant, the company faced anti-trust lawsuits. That’s how you know you’re dominating your category! From 1990 all the way through 2009, lawsuits rained from the sky from the US District Court of Northern Texas to the United States’ FTC to Japan’s Fair Trade Commission, and the European equivalent.

Intel and Microsoft were known as the ‘Wintel’ cartel.

Fast forward to 2021, and Intel just replaced its CEO with its 3rd CEO in 3 years. Intel trades at a 3x market cap to sales multiple, while Nvidia trades at 25x. Apple just announced it was switching to its own M1 chips. Tesla makes its own chips for its self-driving software.

Intel isn’t Andy Grove’s Intel anymore.