The “Better” Trap: Why Comparison Marketing Leads To Fighting For Only 24% Of The Market

When companies compete on features, price, and “brand,” they drive down margins collectively, which limits growth—and the value of the category plummets.

Arrrrr! 🏴☠️ Welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of Category Pirates. Each week, we share radically different ideas to help you design new and different categories. For more: View the mini-book archive | Listen to another category design jam session | Dive into an audiobook | Enroll in the free Category Accelerator email course

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

Let’s do a little exercise.

We want you to think about anything you want except pink unicorns. No pink unicorns, that’s the only rule. You can think about anything, anything in the whole wide world, just not pink unicorns. You can think about lions. Zebras. Giraffes. The entire Amazon forest, if you’d like. Just absolutely, under no circumstances, can you think about pink unicorns.

Now, Pirate....

What are you thinking about?

PINK UNICORNS!

Want to listen to this mini-book instead? Head to the audiobook version, available to all paid subscribers.

The Pepsi (Pink Unicorn) Challenge

In 1975, Pepsi ran what many marketers (mistakenly) believe to be one of the most “creative” campaigns in history.

The challenge consisted of a single blind taste test.

Pepsi representatives would stop unknowing customers at malls, shopping centers, and other public places and ask them to take a sip of two identical looking cups of cola: one containing Coke, the other Pepsi. The results were then compiled into TV advertising campaigns aimed to convince the general public that more Americans preferred the taste of Pepsi to Coke.

Now, let’s do the same exercise again.

We want you to think about anything you want except Coca-Cola. No Coca-Cola, that’s the only rule. You can think about anything, anything in the whole wide world, just not Coca-Cola.

Now, Pirate…

What are you thinking about?

COCA-COLA!

Legendary writer, Malcolm Gladwell, debunked the “success” of the Pepsi challenge 30 years later in his book, Blink. According to Gladwell, the same people who say in a blind taste test they prefer Pepsi because of its sweetness don’t end up finishing a whole can because they find it too sweet. But nevermind that.

For more than 100 years, Pepsi’s entire marketing strategy has been in comparison to the category king of soda: Coca-Cola. There is almost no finer example than the very first line of dialogue in Pepsi’s Super Bowl LIII commercial in 2020, broadcasted to nearly 4 million people (and viewed who-knows-how-many-millions-of-times online thereafter).

“I’ll take a Coke.”

Pepsi might as well Venmo its entire marketing budget to The Coca-Cola Company.

Why?

Because according to our research, category kings capture the lion’s share of the upside of the category. More importantly, for every $1.00 of revenue growth, category creators generate $4.82 of market cap growth (compared to $1.77 generated for other fast-growing companies).

Over the past 10 to 20 years, has Pepsi’s “better product” marketing strategy been working?

No.

If anything, it has further reinforced the fact that Coca-Cola is the king of the soda category. Pepsi’s market share has been falling for more than a decade—which means, despite the company spending tens of millions of dollars on Super Bowl ads (or enlisting social media stars like Kendall Jenner to represent the brand), these efforts haven’t had any meaningful impact on dethroning Coca-Cola’s leadership position.

According to Nielsen (one of the global leaders in marketing mix modeling), the average dollar spent on advertising brings in only $0.70 of gross profit. This insight was derived from 40,000+ marketing mix models across hundreds of categories, all over the world. The takeaway here is that most companies would be more profitable (or, in Pepsi’s case, just as good of a “sweeter” category alternative) if they spent nothing on marketing at all.

For example, Pepsi’s market share in 1984 was 18.8%.

In 2009, Pepsi’s market share was down to 10%.

Then, in 2018, it was 8.4%.

In 2018, Pepsico spent $118 million dollars on advertising Pepsi, down from $139 million in 2013. Let’s make the conservative assumption that Pepsi spent at least $100 million dollars per year on advertising the Pepsi brand since 1984. That adds up to $3.6 billion dollars. Factoring in inflation and nominal returns from investing in treasuries, let’s call this $5 billion dollars. So per Nielsen, if Pepsi was “average” in its marketing ROI, they returned $3.5 billion back in gross profits on their $5 billion in advertising.

We’d bet the ROI was even lower given (a) all this money was spent on comparison marketing, (b) soda as a category has been in decline for more than a decade and (c) new beverage categories have risen dramatically in coffee (Starbucks, Keurig, Nespresso), energy drinks (Red Bull, Monster, 5-Hour Energy) and so forth.

Comparison marketing isn’t just bad marketing. It’s bad business strategy.

Strategy is often defined as how you allocate scarce resources to achieve the highest return on investment. So the question is: what else could Pepsi have done with $5 billion dollars to get a higher return?

To find our answer, let’s play the “What if I was a Category Pirate?” game.

What if, instead of paying Cardi B to yell OKURRRRRR, Pepsi used all that wasted advertising money and bought a company that yielded a breakthrough business model and a breakthrough data flywheel?

Pepsi could have bought:

Green Mountain Coffee Roasters for $2.5 billion in 2009. This would be 3 years after Green Mountain acquired Keurig, becoming one of the great category creators in coffee. Pepsi then would have had instant distribution into offices (one of the great hidden gems of a direct-to-consumer business), leapfrogging Coke’s “within an arm’s reach” strategy. Coffee palates are also highly predictive of broader beverage palates, so this would have been an amazing data flywheel for Pepsi. (Green Mountain Keurig would later go private for $13.9 billion. Whoops.)

Domino’s Pizza for $1.7 billion dollars in 2005. Pizza is a great business on its own, but it would have given Pepsi yet another hugely strategic distribution arm with delivery drivers all over the US—who could have easily added on a 2-liter of Pepsi and bags of Frito-Lay salty snacks as upsells to every order. Pepsi would have also had access to a burgeoning tech company, Domino’s being one of the leaders in testing self-driving cars for delivery. (Domino’s market cap today is $17 billion dollars. Whoops.)

We can go on and on.

Both ideas are powerful because they would have given Pepsi (a) a new category, (b) new business models and distribution and (c) an amazing data flywheel. Pepsi (and Coke) spend 9-10 figures per year on consumer data. And yet all they really understand is the purchasing behaviors of their distributors, retailer customers, and food service customers. But they don’t have any direct-to-consumer information of consequence.

The devil’s advocate argument here is always, “We would have lost more money if we didn’t advertise the Pepsi brand” or “hindsight is 20/20.” But again we ask, what is the point of doing the worst kind of marketing there is (comparison marketing) in a declining category with a brand/product that likely already has 100% awareness and is no different than it was from before?

If you hold up comparison marketing (which is most of marketing) against a true business strategy lens and instead ask, “Can we generate a higher return elsewhere?” then you get a very different picture.

Most marketers and entrepreneurs spend their entire careers competing for only 24% of the value opportunity of the category.

And just like Pepsi, they don’t even know it.

If the category king earns 76% of the category’s total value, that means everyone else is left to fight over the remaining 24%. Within that remaining 24% is a barrel of brands all trying to “out-better” each other. “We’re cheaper! We’re faster! We’ve got this feature! We’re free for 30 days! We’re free for 31 days!” And so on.

But the moment you decide—or, to say it more accurately, the moment you make the unconscious, unquestioned, unconsidered, undiscussed decision—to compete with a “better marketing / product” strategy, what you’re really doing is competing for table scraps.

You are quietly admitting defeat, and announcing to the world you would be satisfied with second place.

Because your entire existence is rooted in the context of someone else.

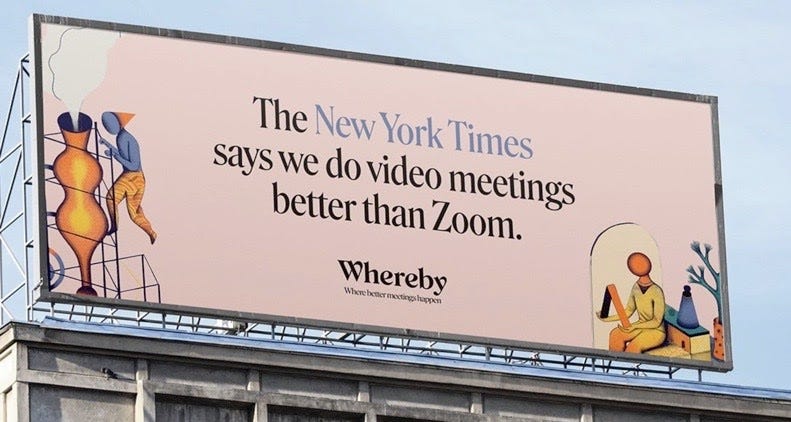

Here’s another example of the “better product” strategy in action:

Ask any run-of-the-mill marketer what they think of this billboard, and they’ll likely say the following:

“It’s so creative.”

“I love the font.”

“It looks sleek and modern.”

“The New York Times? Amazing testimonial!”

(Pirate Christopher read these comments on a marketing community site.)

But ask them if they, themselves, have switched from Zoom to using this “new, better” product called Whereby, and they’ll all say the same thing.

“No.”

Whereby attacks Zoom head-on. Zoom doesn’t even acknowledge Whereby existence.

Which one do you perceive to be the leader?

“Better” is a trap.

Even the world’s most successful, most legendary category designers make this mistake.

Google thought they could build a “better” social network than Facebook called Google+ (which became known as a “sad, expensive failure”).

Microsoft thought they could build a “better” in-store experience than Apple (which resulted in $450 million in losses on the company’s balance sheet).

What’s really happening here is the company is making the unconscious, unquestioned, unconsidered, undiscussed decision to carry their brand into someone else’s category and try to convince the world that their product is “better.” It happens all the time. And it’s always a disaster. But so many people have been recruited into the “better” product and “better” brand cults, this behavior will likely continue—probably for the rest of time.

Anytime a company makes a comparison statement, they are falling into the “better” trap.