Radical M&A Strategy: The Difference Between Accelerating and Consolidating A Category

Why it's worth paying a premium to own the Category King in the emerging or tangentially relevant category.

Arrrrr! 🏴☠️ Welcome to a free edition of Category Pirates. Each month, we publish mini-books that share radically different ideas to help you design and dominate new categories. Thank you for reading, and of course, forward this “mini-book” to any friends you think need to hop aboard the Pirate ship.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and Category Pirate,

In 2006, Google acquired YouTube for $1.6 billion.

At the time, YouTube was barely a year old with just 10 employees. And despite having more than 50 million users worldwide, the startup hadn’t generated any revenue—and didn’t look like it was going to for quite some time.

So why did Google bite?

If you were alive and paying attention to the startup/business world back then, you remember how much backlash and criticism Google received for acquiring such a small, unprofitable company for such a jaw-dropping amount. Wall Street, as well as many of the publications and journalists covering the story, thought Google executives had lost their minds. But fast-forward to 2019, and YouTube brought in $15 billion in advertising revenue—9x more just that year than what Google paid to acquire the site. (Google underpaid for YouTube.) And if YouTube continues at its current growth rate, it could reach $30 billion in revenue by the end of 2021 surpassing Netflix in revenue.

A similar situation happened in 2014, when Amazon acquired Twitch.tv for $970 million. Wall Street and mainstream media were confused as to why a retailer was buying a gaming streaming platform. But fast-forward 5 years, and it’s estimated Twitch generates roughly $300 million in revenue per year (a third of the total acquisition cost)—and that’s not including the “gaming Superconsumer data flywheel” Twitch provides Amazon, helping them sell more retail products to those specific types of customers. Not to mention the likelihood that the long-term-category value in streaming games is colossal. (Matey!)

And, of course, the same thing happened again in 2017 when Amazon acquired Whole Foods for a whopping $13.4 billion. At the time, very few people understood why Amazon would be buying “a grocery store” (it’s painfully obvious today). And yet, just shy of two years later, Amazon generated $18 billion to $20 billion in grocery-equivalent revenue in 2018.

Radical M&A: How To Buy The Future

Salesforce acquiring Slack for $27.7 billion...

Facebook acquiring WhatsApp for $19 billion...

Disney acquiring Pixar for $7.4 billion, Marvel for $4 billion, and Star Wars for $4 billion...

These are all prime examples of Radical M&A: paying a premium to own the Category King in the emerging or tangentially relevant category.

When a company like Salesforce shells out $27.7 billion for Slack, they aren’t buying the brand, the revenue, or the customer base today, as much as they are the company’s leadership position in a category they believe will be much bigger, and much more dominant tomorrow. And since we know Category Kings capture 76% of the economics of the category they own, if the “Company Communications” category continues to grow, it’s reasonable to assume the Category King (Slack) will reap the majority of the rewards.

Said differently: Salesforce didn’t just buy Slack. They bought the leadership position in the exciting, emerging category Slack dominated.

They bought the future. A very different future.

Category Acceleration vs Category Consolidation

At a high-level, there are 2 ways to think about acquisitions that companies make when trying to grow their revenues and category dominance:

Acceleration: Buying the leader in an emerging or tangentially relevant category (or a missing ingredient needed to redesign the current category) to accelerate their position in the future.

Consolidation: Buying a competitor in a slow-growth, shrinking category, in order to bulk-up their position and achieve “economies of scale”.

Wall Street loves consolidation deals because they are familiar and know what to expect. You could play a fun drinking game every time the word “synergy” appeared in the press releases.

Conversely, Wall Street is often perplexed by acceleration deals. These deals are often trashed and followed by a drop in the stock of the acquirer.

But Category Pirates love acceleration deals—and love to buy the dip.

Let’s break down Acceleration vs Consolidation, and then walk through why one is much riskier, yet holds exponentially more potential for value creation than the other.

M&A Category Consolidation

Every consolidation play is a bet on the future being the same as the past.

When Kraft acquired / merged with Heinz in 2015, shares surged more than 33% in the public markets. Why? Because Wall Street and the mainstream business world love deals that make sense on paper. $28 billion in combined annual revenues, complementary product lines, plenty of “synergies” and economies of scale: “Heinz and Kraft are aiming to generate $1.5 billion in annual cost savings by the end of 2017,” CNN Business reported.

Consolidation acquisitions usually cause the market to jump because everybody understands how to value them. Revenue. Cash flow. Margins. Growth rate. EPS. EBITDA. All of these metrics are relatively easy to understand, and when carefully plotted in an excel spreadsheet amount to some sort of cost-savings opportunity, revenue projection, or customer acquisition strategy that warrants shelling out a few billion dollars. “Kraft shares surged more than 33% Wednesday,” following the news of the Kraft Heinz merger in 2015.

People “got it.” (Or at least they thought they did.)

The problem with consolidation deals, however, is that they are market share grabs and cost takeout strategies. And if you are consolidating a slow-growth/shrinking category (Kraft & Heinz both with massive product lines of processed foods—an increasingly unpopular category of food), it doesn’t matter how much of the market you own. Even Kraft Heinz agreed, eventually spinning off several brands in declining categories like natural cheese and nuts.

When the category is dying, you are too.

4 short years after the Kraft Heinz mega-merger, it was deemed by the New York Times a “mega-mess.” The article goes on to explain the company took a $15.4 billion write-down in February, 2019, slashed its dividend by a third, reduced the value of its assets by $1.22 billion in a single month, and the company stock plummeted 51% between 2018 and 2019.

Consolidation plays look great in the short-term, but rarely play out successfully in the long term. Investing in Kraft Heinz is effectively a bet that says categories like gelatin desserts (Jello), sugary powdered drinks (Kool-Aid), and pre-Starbucks/Keurig/Nespresso coffee (Maxwell House) have their best days ahead.

Do you believe that’s true?

If not, then why bet on the past when you can bet on the future?

M&A Category Acceleration

Acceleration plays are a bet the future will be different from the past.

Tomorrow will not be a continuation of today.

Acceleration deals are the complete opposite of consolidation deals. They are hard to value, have absolutely nothing to do with current-day revenues (Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 billion in 2012 before it had generated even $1), and have more to do with where the world is headed—not where it is today. Acceleration deals do not “pencil out” the way consolidation deals do because it’s impossible to build a financial model for something that doesn’t exist yet. So, when a company acquires a Category King in a small-but-rapidly-accelerating category, most of Wall Street and the mainstream business media laughs and calls the company executive idiots (before going and buying more Kraft Heinz stock).

It isn’t until a few years later that the deal makes complete sense. The emerging category has become the dominant category, the category creator has been declared King, and the way the world was is no longer the way it is.

Where would Google be today if they didn’t own YouTube?

Be The Best | Be The Winner | Be DIFFERENT

In a previous letter, we wrote about the 3 types of companies (and creators) that exist in the world.

Be The Winner: Market Share Maniacs with no goal other than to beat their competitors and be the #1 market share leader (believing things like “brand equity” will be the reason customers pick their products off the shelf).

Be The Best: Companies that want to be seen in the market as having the “best” product, service, or technology (innovation & R&D focused, but exclusively through the lens of having the best tech/product for the sake of being able to win comparison debates against existing competitors).

Be DIFFERENT: Companies that end up writing (creating a new category) or rewriting (redesigning an existing category) the rules of the game and driving all the “Be The Winner” and “Be The Best” companies either out of business or out of relevance by creating a different future.

Let’s break each M&A strategy down through a category lens.

“Be The Winner”

“Be The Winner” companies are notorious for executing M&A strategies with the singular goal of consolidating their current category—which is why you tend to hear about one big oil company acquiring another medium-size oil company (same category), or one big pharmaceutical company merging with another big pharmaceutical company (same category). It’s common for these acquisitions and/or mergers to emphasize cost-cutting, efficiency improvements, and other “synergies” that make sense on paper but are usually a nightmare to integrate.

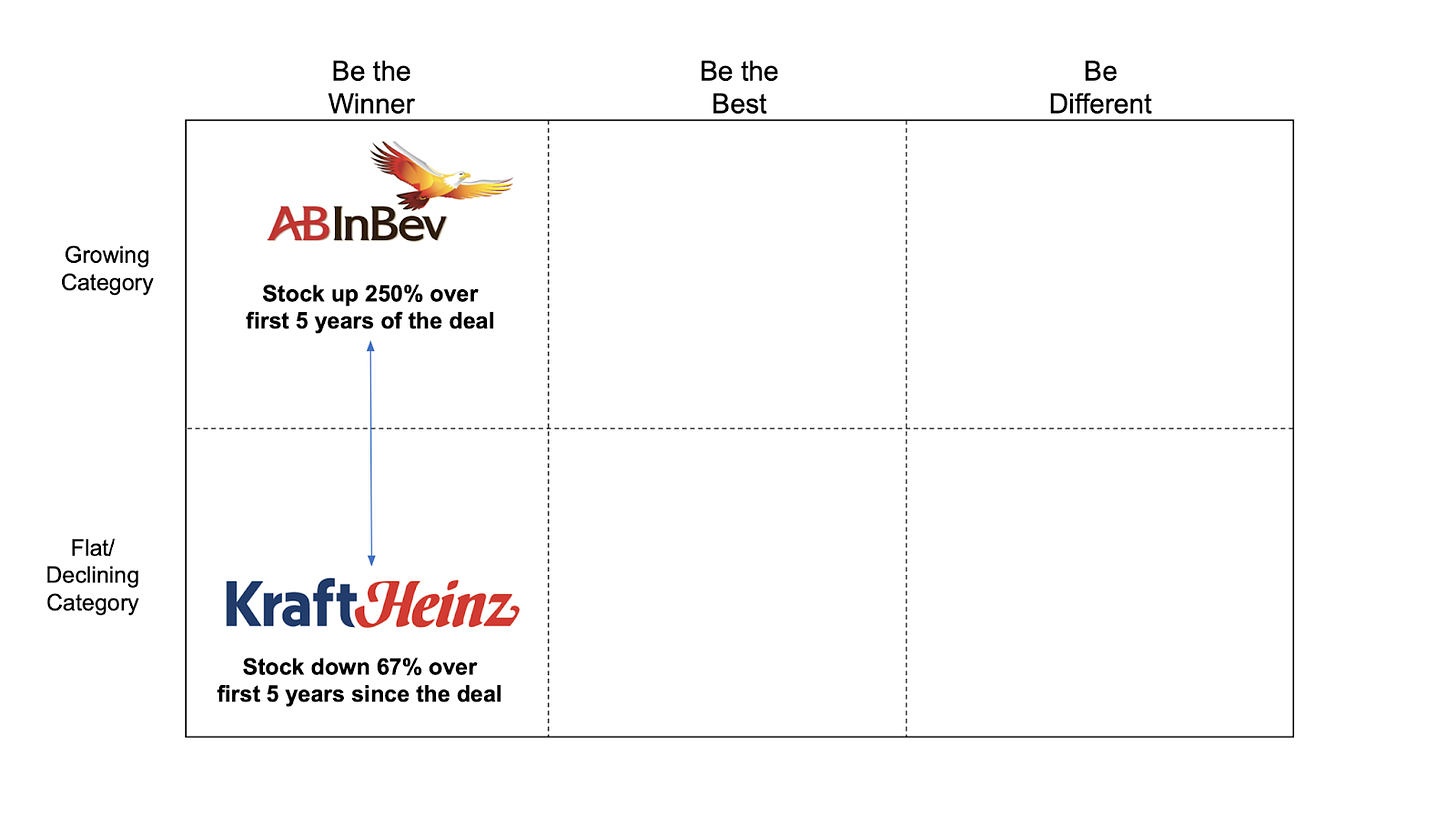

If you are going to do a “Be the Winner” M&A deal, you want to do so in a growing category with a 20 year tailwind. For example, in the case of Kraft Heinz, Warren Buffett partnered with the great Brazilian investors 3G, who also did the Anheuser-Busch InBev deal. Global beer continues to be a growth category as beer generally grows with population and real pricing power—unlike beverage categories like Kool-Aid. Consolidation in a growing category means you are accelerating your existing leadership position, whereas consolidation in a flat/declining category means you are trying to own more for the sake of “more,” regardless of what the future holds for your category and business.

“Be The Best”

“Be The Best” companies are usually “bolt-on” acquisitions where a company recognizes a particular missing piece of technology, team (“acqui-hire”), product/service, or business model that allows them to cement their position as a market leader.

When Apple bought Beats By Dre, it was primarily for their streaming music service, not just the headphones hardware—which Apple already had. Apple paid $3 billion for Beats By Dre in 2014, but in 2020 was estimated to have 72 million Apple Music subscribers generating $4.1 billion in revenue. It is a great example of a Category King recognizing its legacy business (iTunes) had seen its best days behind it, but made smart acquisitions and bets to ensure its leadership held on as the category evolved.

Using our 8 Differentiation Levers framework is a great way to spot these missing puzzle pieces, and can reveal where making a strategic acquisition can help you accelerate (or keep) your leadership position.

What is key, however, is to make sure you’re buying tech, teams, products, or business models that have strong tailwinds—like Apple did with streaming music. For example, when Verizon bought AOL and Yahoo for a combined $9 billion dollars, both businesses clearly had their best days behind them—as evidenced by Verizon throwing in the towel and selling both businesses to Apollo for half of what they paid. Verizon could not figure out how to leverage AOL or Yahoo to drive its core wireless business, much like AT&T could not figure out how to leverage HBO to drive its own wireless business.

Back to competing and comparison for them!

“Be DIFFERENT”

“Be DIFFERENT” companies, on the other hand, very rarely (if ever) make acquisitions with the goal of consolidating their current category, and instead look to acquire Category Kings in new, emerging, and tangential categories to scale and/or expand their leadership position horizontally. In most cases, these are smaller, earlier-stage companies where there is more exponential upside potential.

We already discussed one of the most legendary examples, which is Google buying YouTube. But there are many more that fit into this space, including Amazon buying Whole Foods (creating the future of true omni-channel retail), and Tesla buying Solar City (home energy revenues recently exceeded its costs in the most recent quarter). In each case, the acquirer was buying a very different future—and in the short term, very few people understood why.

Perhaps the best cautionary tale here is one of the largest M&A deals in business history: AOL acquiring Time Warner for $182 billion dollars in 2000. AOL was clearly trying to be different, but the problem was they bought the past, not the future. HBO (owned by TimeWarner) still continued its run of prestige television including the Sopranos, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and The Wire, leading all the way up to Game of Thrones (and all of these assets remain to be amazing evergreen content today), but TimeWarner’s business model was still rooted in the past.

Consider a much smaller acquisition AOL could have made that very same year: Netflix.

Remember, Netflix tried to sell itself to Blockbuster for $50 million dollars in 2000.

Today, Netflix is worth $230 billion dollars in market capitalization.

Executing a “Be DIFFERENT” acquisition is not easy, even when it is right in front of you.

One last example to drive the point home:

In 2010, Toyota owned 11.5 million shares of Tesla (post-split) when they were partnering together to build hybrid RAV-4s.

Tesla’s Fremont plant is a former Toyota-General Motors joint-venture plant. In 2017, Toyota sold their Tesla shares for $0.5 billion dollars—nearly 10x its original investment. The idea was for Toyota to double down its bet on Hydrogen fuel cells (which Elon Musk has called “mind-bogglingly stupid”), and was determined to compete with Tesla.

Had Toyota held onto those shares, they would be worth $7.5 billion dollars today. And had Toyota learned from Tesla, perhaps they would own the inside track on the “best” technology.

Or, had Toyota acquired Tesla during its darkest moments when they were days away from bankruptcy, perhaps Toyota and Tesla together might be worth a trillion dollars in market capitalization today (versus Toyota’s $250 billion dollar current market cap).

Depending on which type of M&A strategy you choose drastically changes the value you are able to generate.

Before executing any M&A strategy, you must ask yourself the following question:

“What is our assumption about the future, and why?”

If you’re Google and your assumption in 2006 is that online videos & video search are going to become less valuable in the future, you don’t buy YouTube.

If you’re Facebook and your assumption in 2012 is that mobile photos are going to become less valuable in the future, you don’t buy Instagram.

If you’re Amazon and your assumption in 2014 is that online gaming and live streaming are going to become less valuable in the future, you don’t buy Twitch.

However, if you DO believe the future is going to be DIFFERENT than the way things are today, then the price is almost irrelevant. How do you value the future? You don’t. You can’t. You can make assumptions and guesses. You can have a team of spreadsheet wizards whip up a model. But 99% of your bet isn’t rooted in revenue today. It’s based on category revenue potential tomorrow—which is what makes it a risk (and why acceleration acquisitions lead to exponential upside).

M&A Acceleration Strategy: Play The Breakthrough Game

In a previous letter, we wrote about how you can spot the future and anticipate headwinds and tailwinds by playing The Breakthrough Game.

In the context of Radical M&A, the question you want to ask yourself here is, “What Category King could we acquire that would put anything we tried to build in that category out of business?” For example, when Microsoft bought LinkedIn for $26.2 billion, how do you think they arrived at that number? LinkedIn’s revenue in 2016 was $3.7 billion.

Somewhere in a cubicle we can hear a number cruncher muttering, “Who would pay a 7x multiple for a business social network? That’s stupid.”

Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn doesn’t make sense on paper—until you start playing The Breakthrough Game and imagining all the strategic adjacent opportunities. LinkedIn is the dominant Category King in the “business social network” category by a mile. And for Microsoft, the Category King of “software for white-collar knowledge workers,” this is a treasure trove of data: where they work, what their job title is, what training and skills they have, where they went to school, and so on.

To Microsoft, this data flywheel is invaluable.

In the long run, paying a 7x multiple will probably seem cheap.

Do You Want To Bet On The Past Being The Same? Or The Future Being Different?

We are Pirates, which means we aren’t interested in consolidation plays.

A lot of people do it. Some do it well.

But we’re not interested in betting on the past and achieving short-term “economies of scale” or revenue strategies dependent on reducing customer value with the goal of fluffing margins.

We’re in the business of betting on DIFFERENT.

We want to be part of where the world is going, not where it’s already been.

There’s an amazing scene in The Social Network, the movie about the infamous lawsuit between Mark Zuckerberg, co-founder Eduardo Saverin, and the Winklevoss twins, where determined angel investor and Napster founder, Sean Parker, summarizes the power of betting on the future.

“I brought down the record companies with Napster,” says Parker.

Saverin tries to correct him and says, “Wait, sorry. You didn’t bring down the record companies. They won.”

“In court,” says Parker.

“Yea,” says Saverin, confident he’s just put Parker in his place.

To which he responds, “Do you want to buy Tower Records, Eduardo?”

Silence.

Napster, illegal as it might have been, fundamentally changed the entire trajectory of the music business—and even the broader entertainment industry as we know it. A breakthrough had occurred. And once Napster caught fire in college dorms and Internet chat rooms, the future of streaming was certain—even if it took most people another decade to acknowledge it.

Arrrrrrr,

Category Pirates

P.S. - If you found this mini-book valuable, we encourage you to check out some of our other free favorites:

To access our entire mini-book library, become a paid subscriber 👇

This article got me thinking about ways to spot current and future trends to buy the future.

As of writing this comment in Sep 2022, some current trends I can think of revolve around the metaverse, web3, AI generated anything, and nuclear power.

What other trends can you think of? What are the best ways to gather information on them?